Shopping Bag

0

- No products in the cart.

Thailand has made great progress honing its coffee-growing industry in recent years.

Growers are producing excellent specialty coffee as judged by professional tasters, but apart from a couple of internationally known brands such as Doi Chaang Coffee, a visitor from abroad would’ve been hard-pressed to recognize any brands among the exhibitors at the 1st ASEAN Coffee Industry Development Conference (ACID).

Why is that? And more importantly, can anything be done to put Thailand-grown coffees on the world map? According to Varri Sodprasert, president of the Thai Coffee Association and the keynote speaker at the conference, global recognition is impeded by several mutually compounding factors.

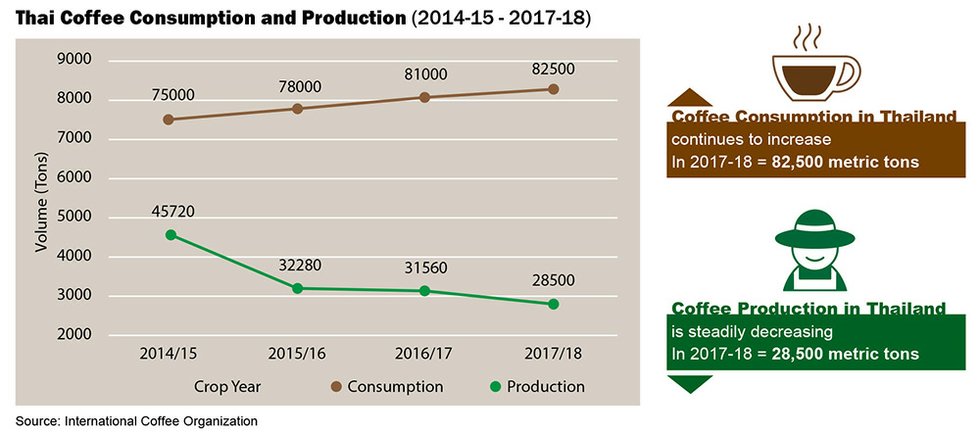

Topping the list is the fact that – just like most of its neighbors – Thailand has transformed into a coffee-drinking society. “We consume more [coffee] than we actually produce. Previously a coffee exporting nation, Thailand has turned into a coffee-importing country,” Varri said. Indeed, consumption has steadily increased over the past years as domestic production of both arabica and robusta decreased.

In 2017-18, the Southeast Asian nation of 70 million people consumed 82,500 metric tons of coffee, while producing only 28,500 tons. “As these figures show, Thailand needs to import raw coffee from neighboring countries because our own production is insufficient to even supply the local market,” Varri reiterated.

The slump has been particularly steep with robusta, which is primarily grown in Thailand’s southern provinces of Chumpon, Ranong, Suratthani, and Nakorn Srithammarat. “At present, our robusta production has contracted to only 25% of its former maximum volume,” Varri said. Arabica hasn’t fared much better. The country currently produces 9,800 tons of the crop annually, almost exclusively grown in the mountainous northern regions. This yield is of course a far cry from the gigantic amounts shipped by Vietnam and Indonesia. The former, estimated to produce 30 million 60-kilo bags in 2018-19 is now the second-largest producer globally after Brazil; and Indonesia is at fourth place.

The reasons for the overall contraction are manifold, but perhaps the most important is a severe labor shortage. Farming and harvesting coffee is labor-intensive, relying mostly on seasonally hired workers. “It’s therefore not a simple matter of increasing planting areas. That will only reinforce the labor shortage problem and solve nothing,” Varri asserted. “We prefer the farmers to understand that the global coffee market has changed.” Instead, Varri wants farmers to improve their environmental standards, as that “will automatically increase yields and achieve good crop prices.”

This is where ASEAN could lend a helping hand. “For example, Indonesia planted coffee long before [Thailand] and thus can teach us about setbacks and problems that they’ve successfully tackled,” Varri said. The most important collaboration, she added, would be an information, knowledge, and exchange of know-how between ASEAN member countries. That also would include environmental protection practices, for it’s not only the quality of our coffees that’s important to Varri but also how Thailand can achieve and implement sustainable farming, she explained. “We have stepped forward to cooperate with ASEAN and don’t see our fellow ASEAN members as competitors; but rather as partners and what we can learn from them,” Varri said, adding, “We ultimately aim at making ASEAN a global coffee hub, both in terms of production and consumption.”

Viewed from that perspective Thailand is in an enviable position. The country is located right smack in the region’s geographical center. “We also have modern production plants with well-trained staff in addition to excellent logistical facilities that can handle product imports and exports not only within Asia but indeed to and from any corner of the world,” Varri observed. And that, she insisted, makes Thailand “an excellent choice for investors, whether they want to build a plant or just trade.”

In addition, the country has enacted a favorable import tax structure, with a tax of green beans from other ASEAN countries at around 5% of import value. Unfortunately, this does not apply to coffee shipments from outside ASEAN. “There are strict quotas, and if exceeded, the import tax is very high,” Varri admitted. “But we’re trying to address that [with the government]. After all, Thailand has changed from an exporting country to an importing country, so the relevant regulations have to be adjusted.”

None of that explains why Thai specialty coffee brands are so thinly represented outside the country. Varri suggests a lack of know-how among local brand owners is foremost to blame. Specialty coffees are invariably produced by small village cooperatives and – often enough – single-family businesses.

“They may know how to market their products in Thailand but lack marketing development skills internationally,” Varri said. These small brand owners aren’t familiar with the myriad of regulations enacted in foreign markets, nor do they have the marketing savviness or foreign contacts to pull it off.

“If they want to develop an international business, they will need to study the requirements… and that is easier said than done,” Varri said but added that this would be an area where the expertise of other ASEAN member states such as Indonesia and Vietnam could be tapped.

Free Shipping On All Orders $200+ |